Update: As someone on Reddit noticed, you could avoid the need to modify Google Chrome’s start up and still accomplish the below by simply redirecting the request to an HTTP web server that serves the static JSON response, instead of redirecting to a Data URL. This would mean you have to have a server set up, and the project would have more moving parts, but no modification to browser start up would be needed.

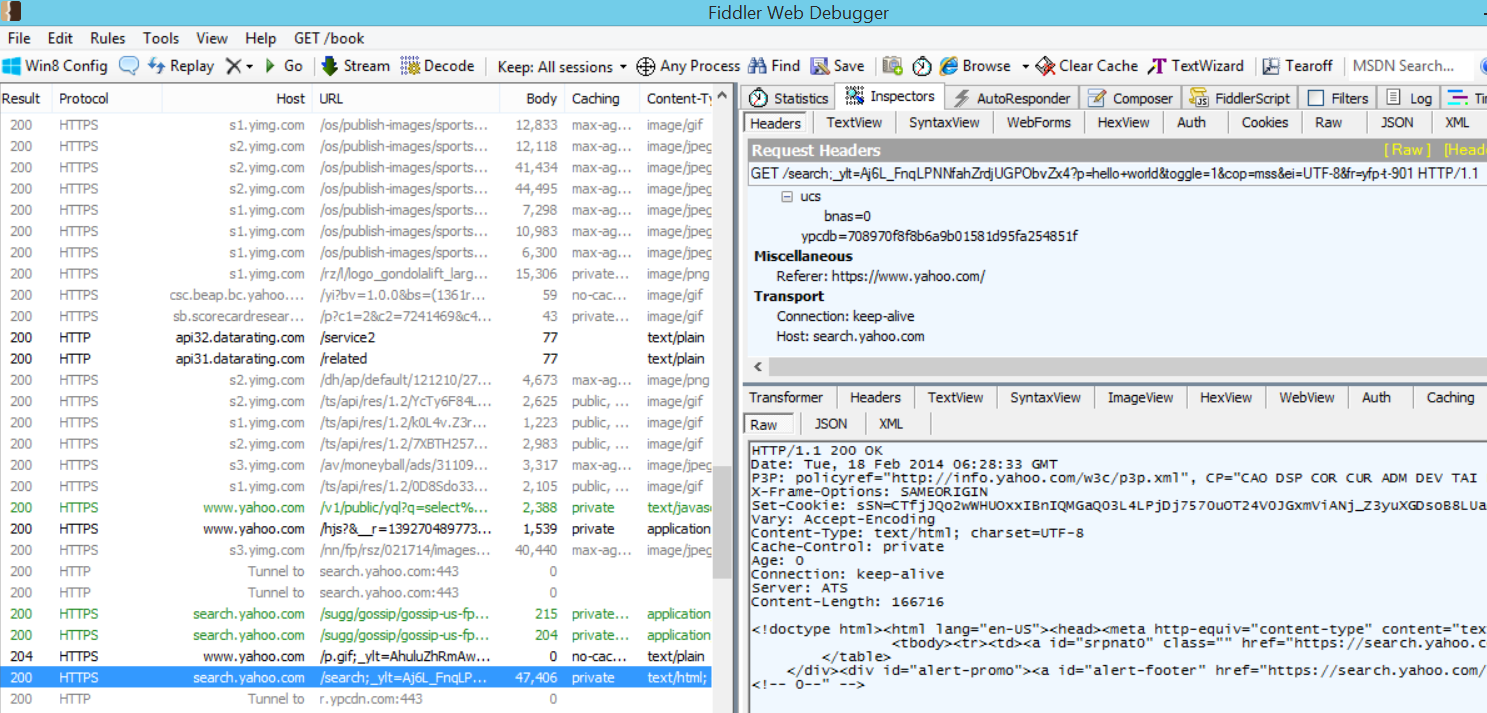

After releasing Trivia Cracker, a Chrome extension that automatically selects the correct answer for you while playing the mega-hit game Trivia Crack, a lot of people had opinions to share. Some were positive, some negative, but one comment in particular caught my eye:

An opportunity to help out a young computer scientist, and with his love life nonetheless! It’s not often that the solution to a tough computer science problem could result in not just a great first date, but maybe even wedding bells and kids. Naturally, this piqued my interest — at all levels. The hacker, mentor, and hopeless romantic in me were all hooked. So I responded to the comment and waited to hear back.

To protect my creative high school friend’s privacy, I’ll refer to him as Bob for the remainder of this post. And let’s call the girl Bob wanted to ask to prom Alice. Given the time until prom and Bob’s previous knowledge of web development, we decided that, to make the deadline, I would develop this Trivia Crack wingman-program for him. But, I did request a few things in return:

-

If Alice said yes, Bob would email me a photo of the two of them on prom night.

-

At some point in the future, when Bob feels ready, he should go back and look at the code for this project and make sure he understands how it works. To prove he understands it all, he should modify it to ask a different question with different possible answers.

-

If Alice and Bob get married, they should name their first born child after me.

Just kidding about that third part.

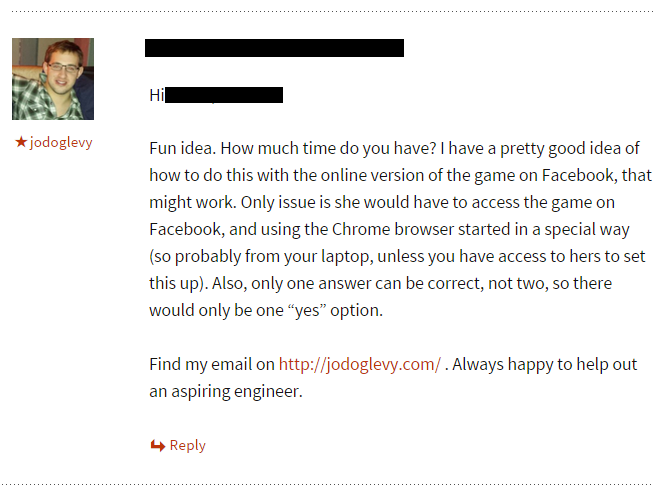

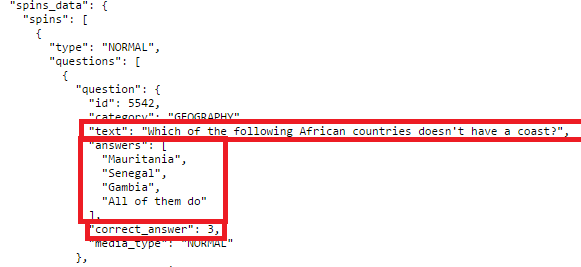

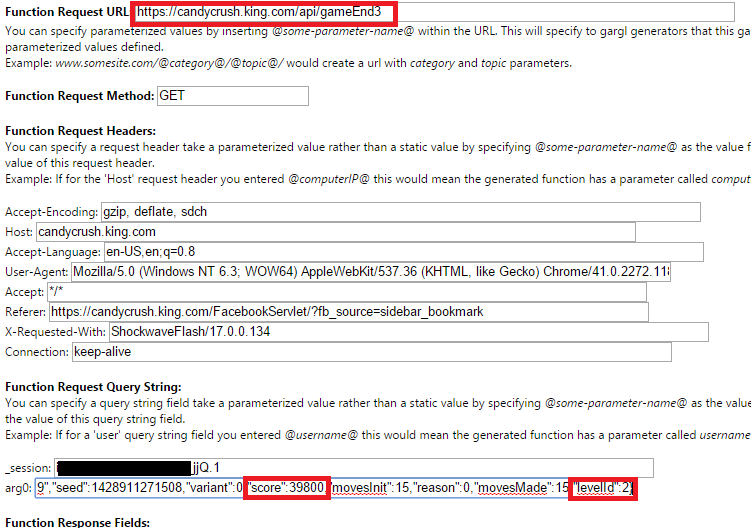

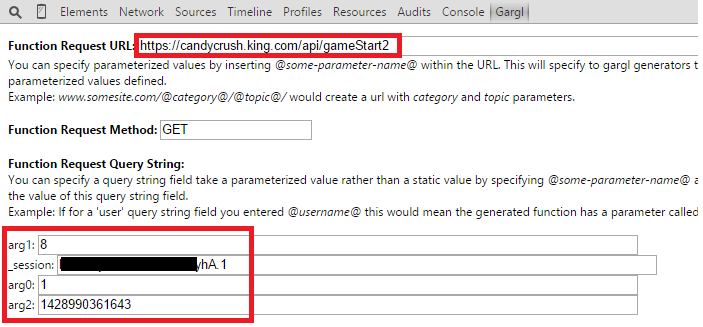

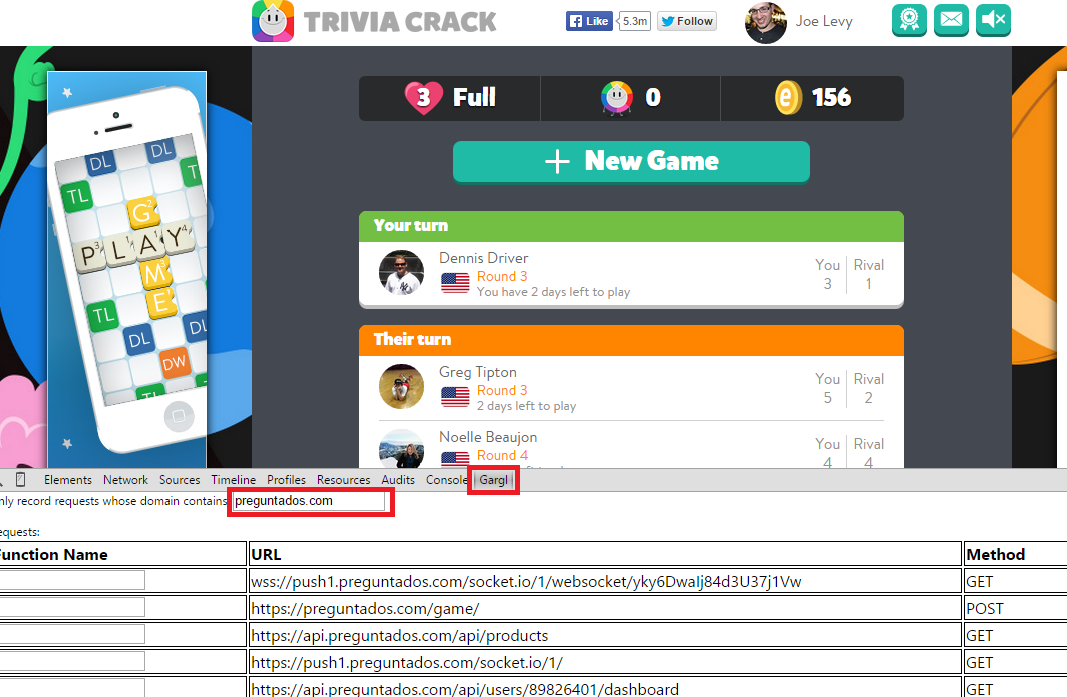

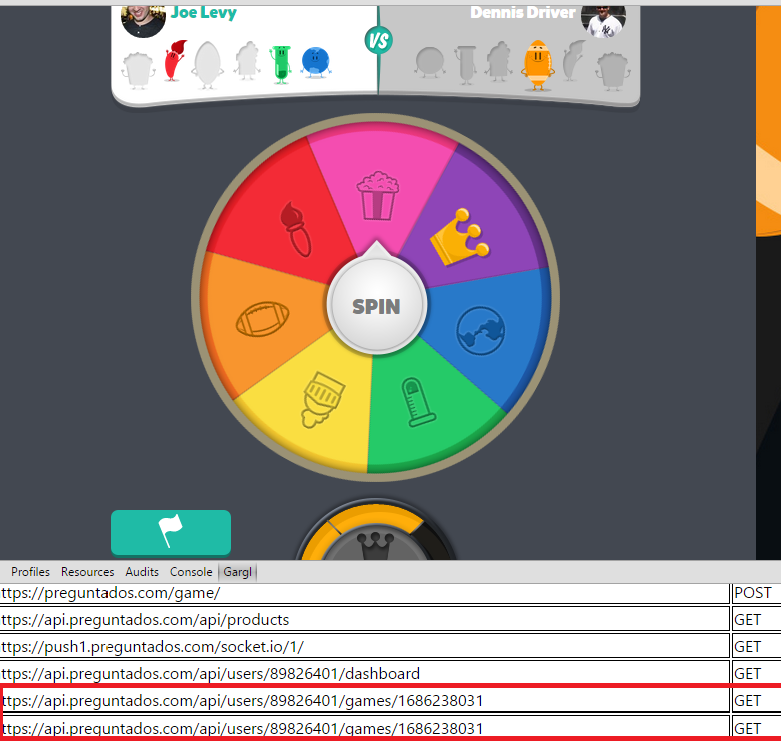

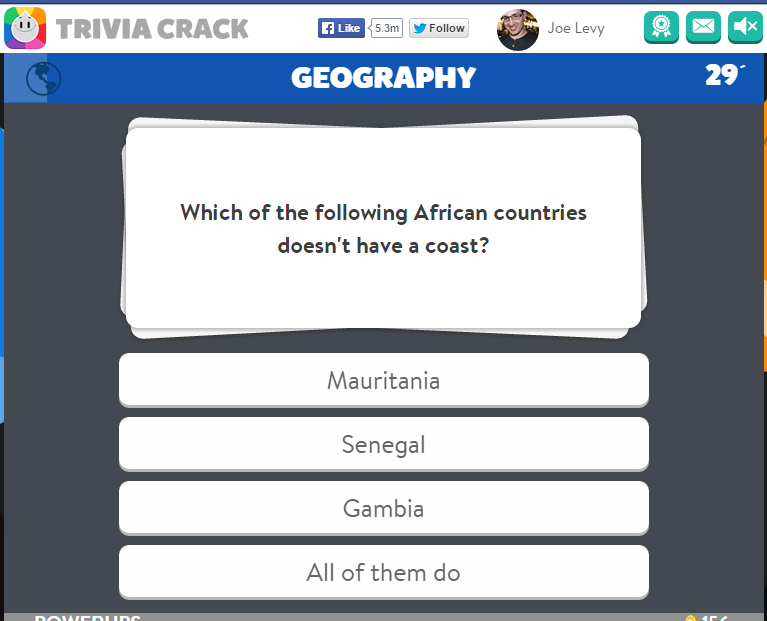

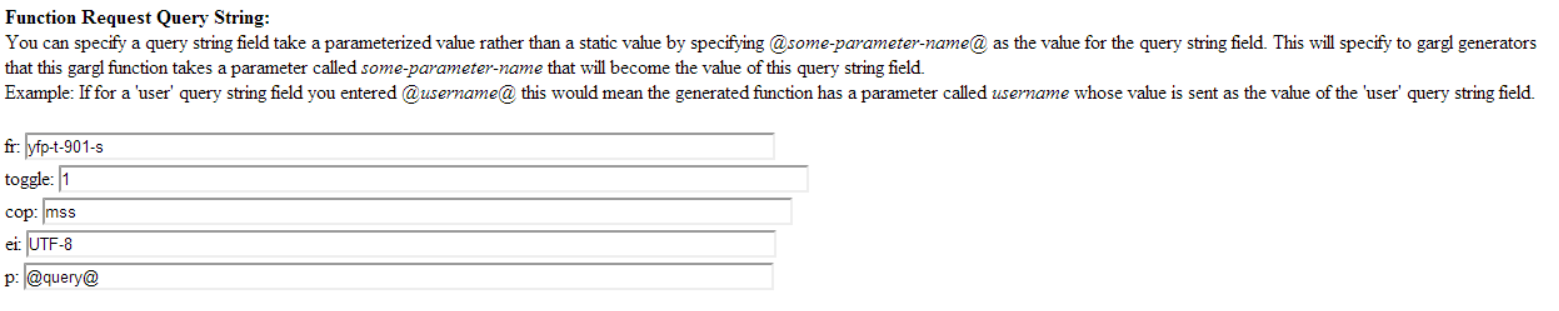

After we agreed on the terms, it was time to get cracking. To summarize, the goal was to modify Trivia Crack so that Alice could play the game like she normally does, not knowing it was any different, but the question she’d be asked would not be one of trivia, but a prom proposal. From my previous work cracking Trivia Crack, I had a pretty good idea of how the Trivia Crack Facebook client works in its communication with the Trivia Crack server API. Namely, I knew that when a new game is started and after the user answers correctly, the Trivia Crack client requests from the server the next question to ask the user. The server responds with not just the question, but all the possible answers to the question, as well as the correct answer. Here’s an example of the response body the server sends:

Yes, Trivia Crack is breaking the cardinal rule of “never trust the client” here by sending the correct answer to the client, and I talk more about the consequences of that in my blog post on Trivia Cracker, but for now lets focus on prom night!

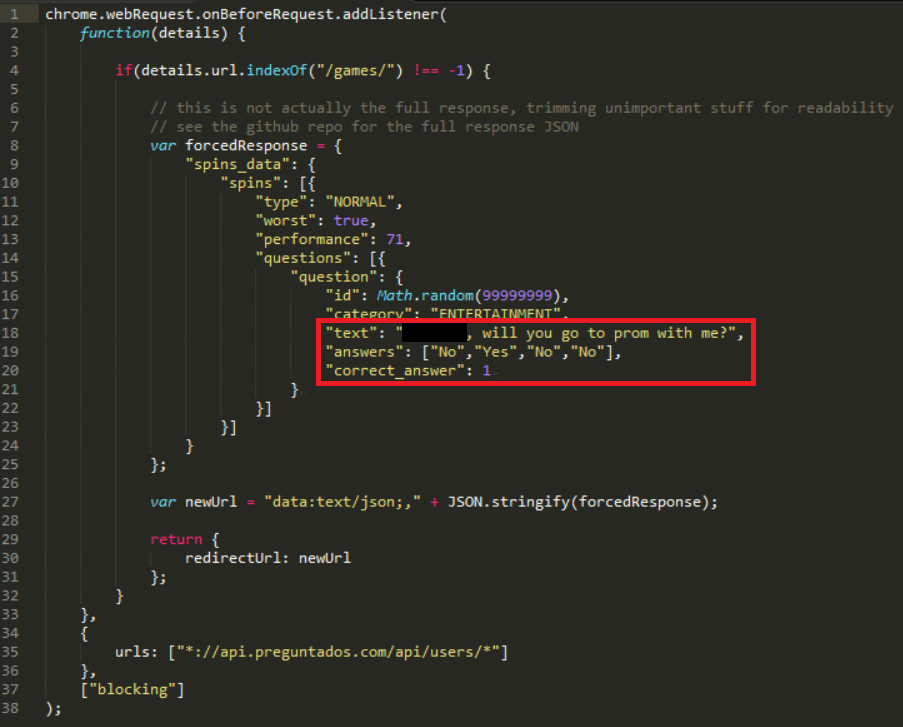

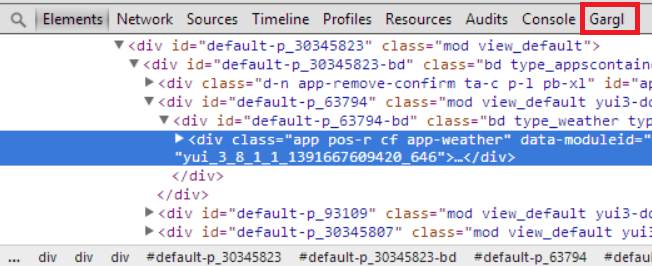

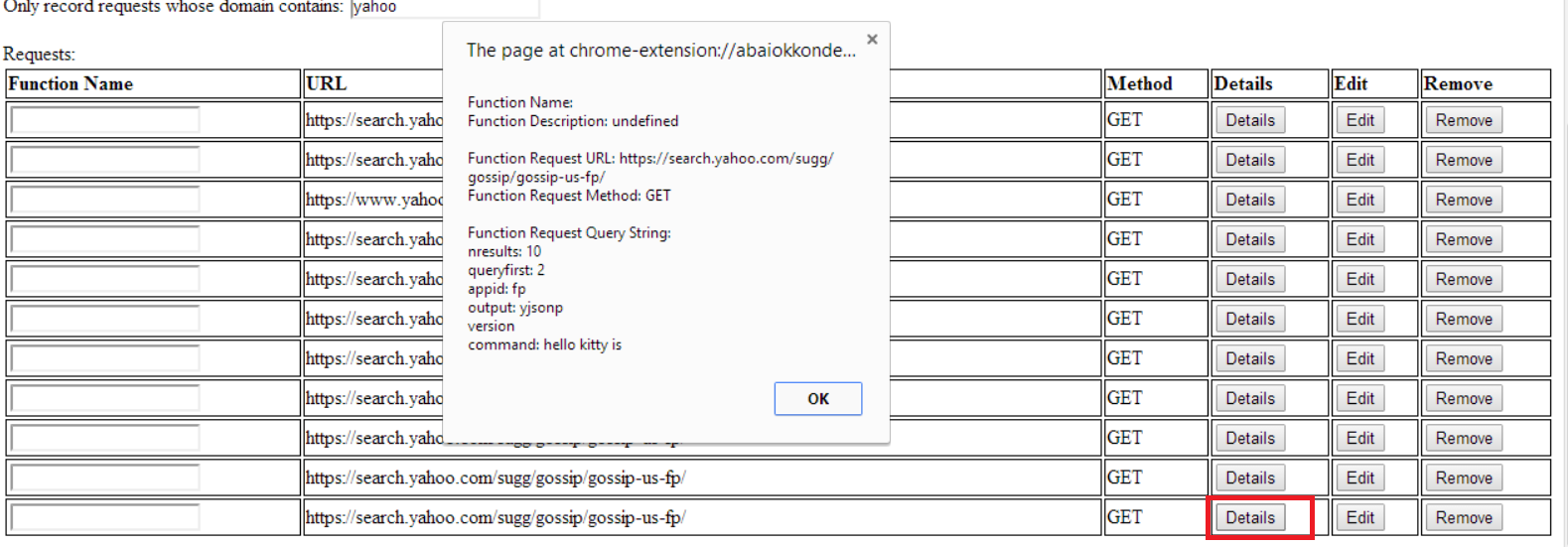

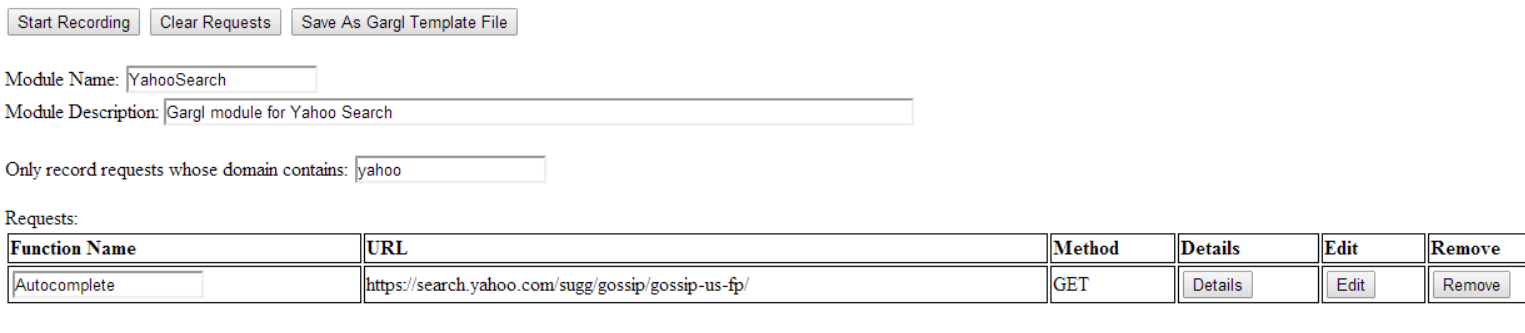

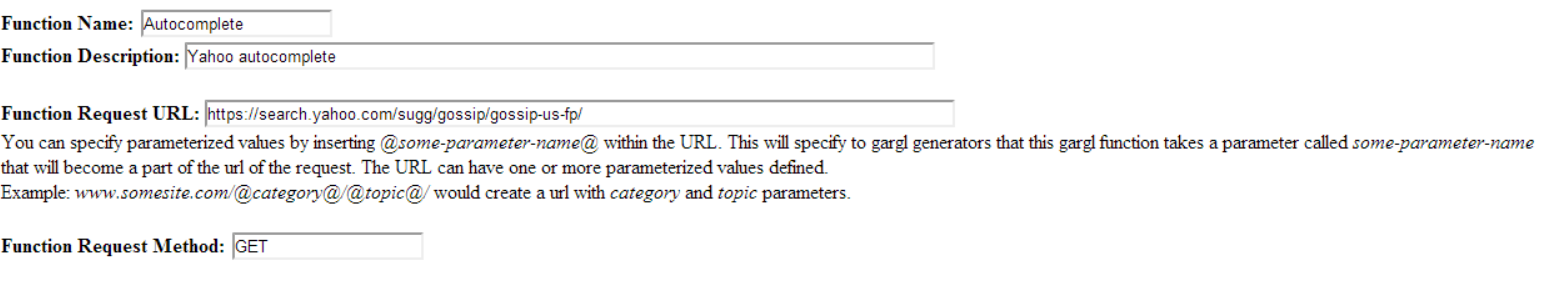

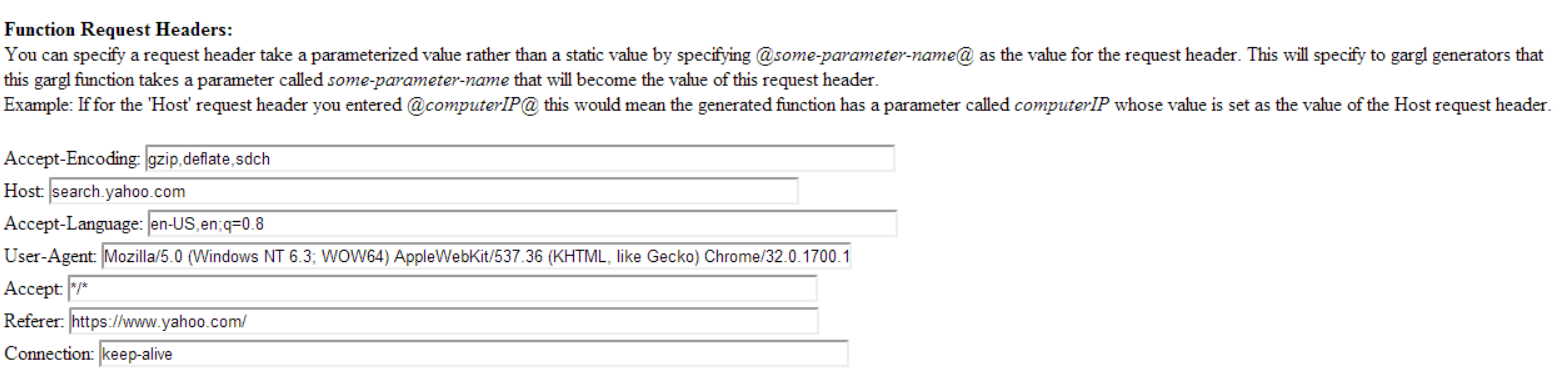

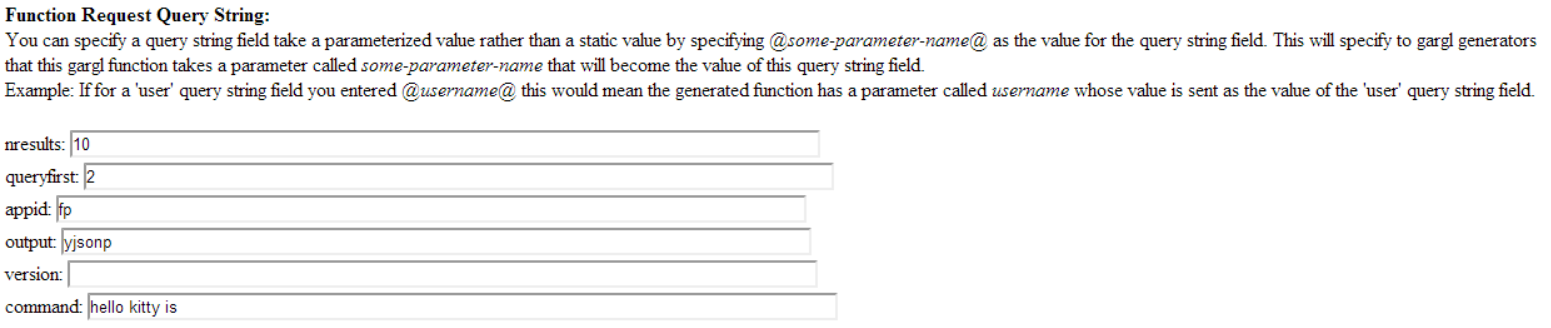

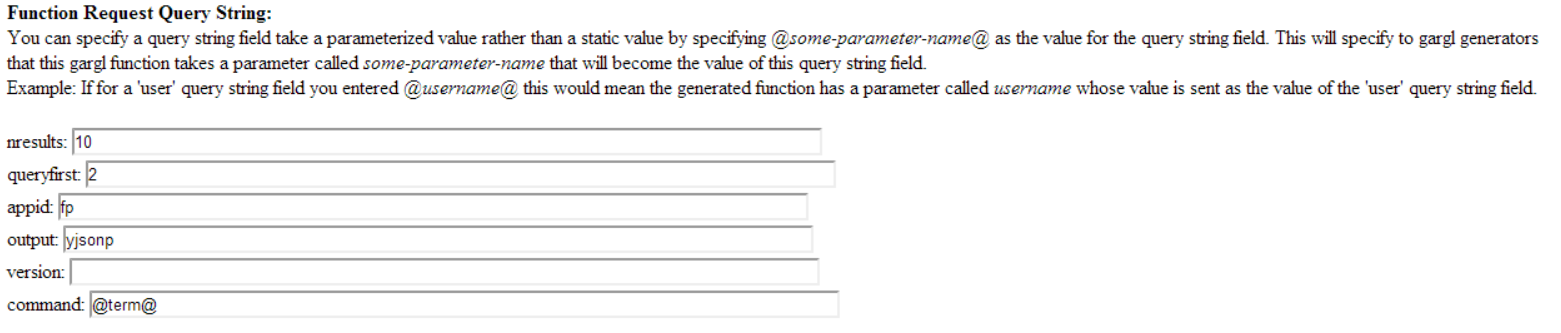

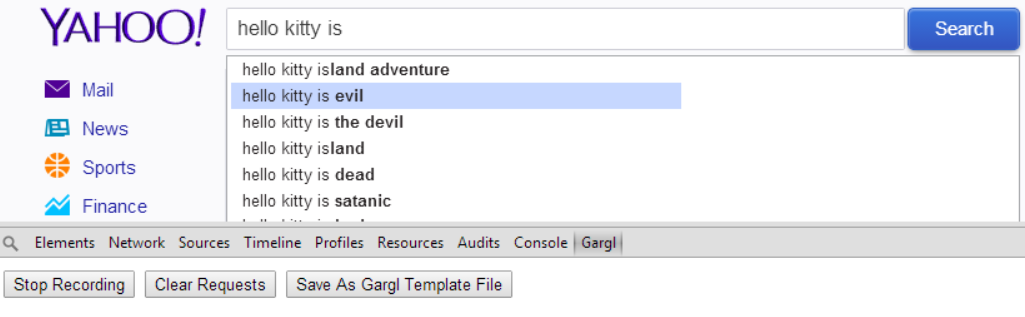

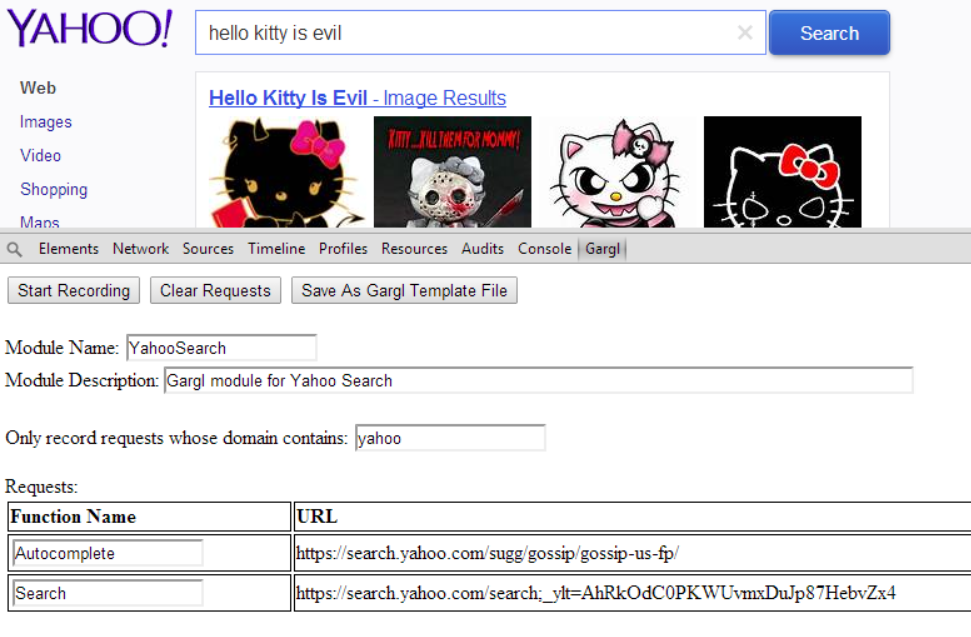

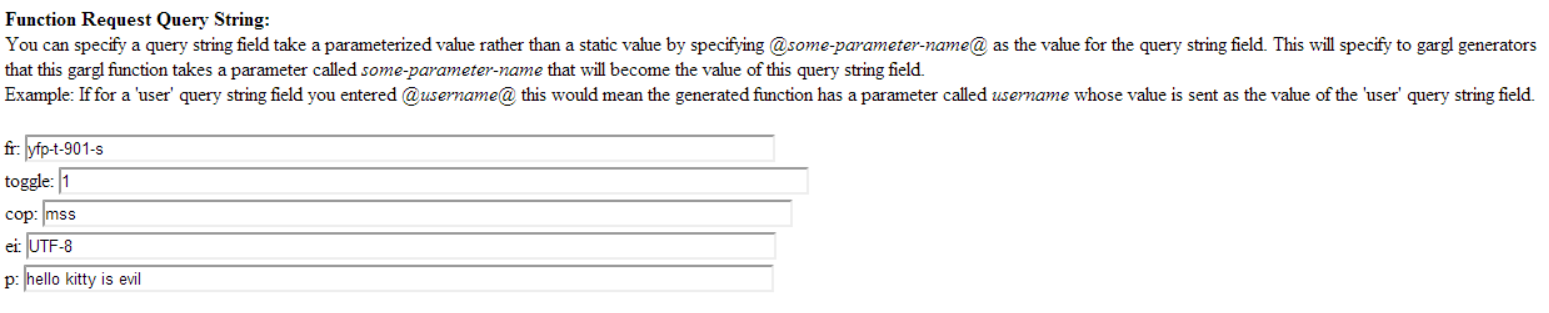

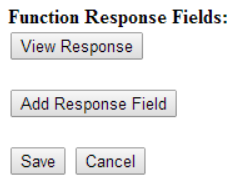

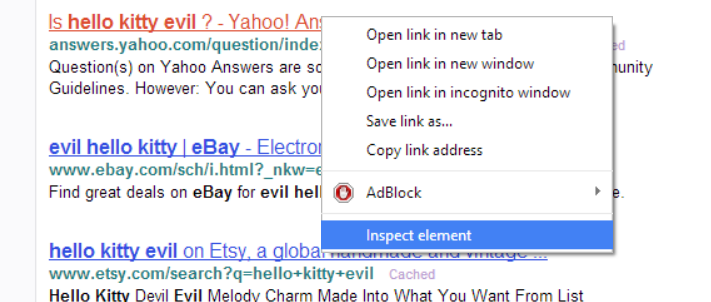

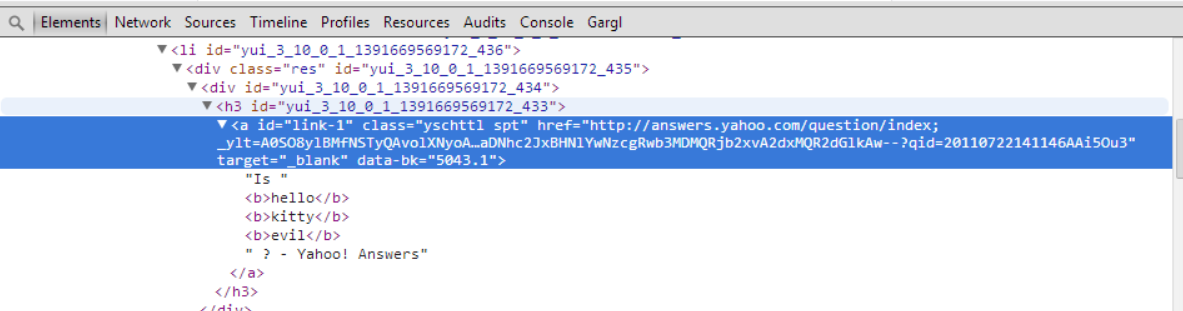

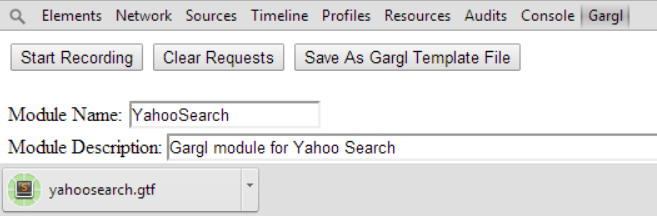

Knowing a fair amount about Google Chrome extensions, I knew that Chrome extensions have access to Chrome’s webRequest API. This API provides the ability to redirect outgoing requests from the browser to alternate URLs. I also knew that you can turn a JSON payload into a Data URL using the data:text/json;,{…} format. Together, these functionalities meant that I could, through a Chrome extension, man-in-the-middle the Trivia Crack get next question API response to be any JSON payload I desired. And it just so happened that this was a perfect way to get Trivia Crack to ask Alice to prom. Throwing this together actually only took a few lines of code — almost the entire “response override” functionality of the Chrome extension is below. You can also check out the entire project’s code on GitHub if you’re interested.

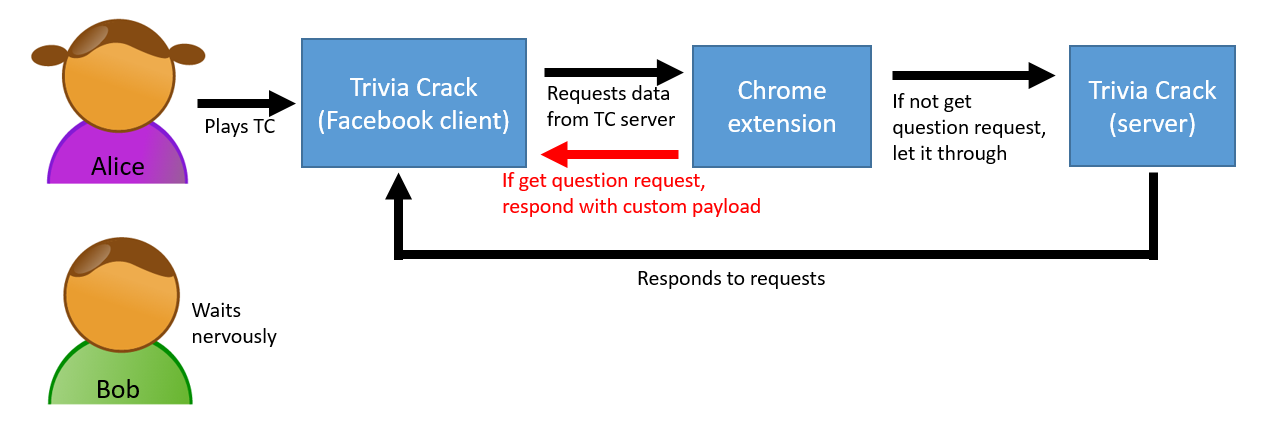

As you can see from the snippet above, all I’m doing is adding a listener for any HTTP requests in Chrome to Trivia Crack’s get next question API. When that listener fires, I am giving Chrome a static JSON payload with the custom prom-related question / answers, as a Data URL, and asking Chrome to redirect the request to this URL instead. Here’s a diagram of the data flow:

Simple, aye? If you wanted to make things more robust, instead of doing a “static” man-in-the-middle (hard coding the custom response), you could do a dynamic man-in-the-middle — when the listener fires, make your own request to Trivia Crack’s get next question API, modify the question and answer parts of the response you receive, and then redirect to that as a Data URL. Due to Chrome’s webRequest API being synchronous you’ll have to make the AJAX request to Trivia Crack synchronously (SJAX?), and while synchronous AJAX is discouraged, it is possible to do and should be ok in this case considering this all happens on a background thread rather than the main browser thread. But anyway, this was just a quick weekend project, so I hard coded the response. Dijkstra forgive me.

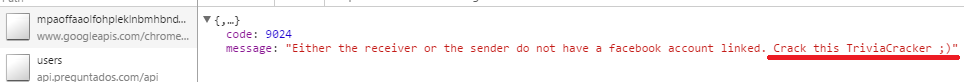

Well, it should have been that easy. But because Trivia Crack uses cross-origin resource sharing (CORS) to make AJAX calls across domains, loading this up in Chrome and trying to overwrite the response resulted in an error:

The request was redirected to ‘data:text/json;,{…}’, which is disallowed for cross-origin requests that require preflight.

To get around this hurdle, since this project only needed to work once rather than be truly ship-able product, I modified Chrome’s start up to run with the –disable-web-security option specified. This flag relaxes some of the requirements of same-origin policy and CORS, allowing the response override to work. You wouldn’t want to keep this flag enabled for your daily use of Chrome, but for a quick prom-proposal, it’ll do…unless your potential date is very computer-security conscious, that is.

What’s scary about this is I wouldn’t have needed the –disable-web-security flag to do this if Trivia Crack wasn’t using CORS. This means any website that doesn’t use CORS can be man-in-the-middled by a Chrome extension, with no changes to Chrome’s start up needed. You may think you’re talking to your bank’s website, when really there’s a Chrome extension modifying your requests and the banking website’s responses, recording all of your sensitive data as it does so. Just another reason to be very careful about which Chrome extensions you trust, and what permissions you trust them with.

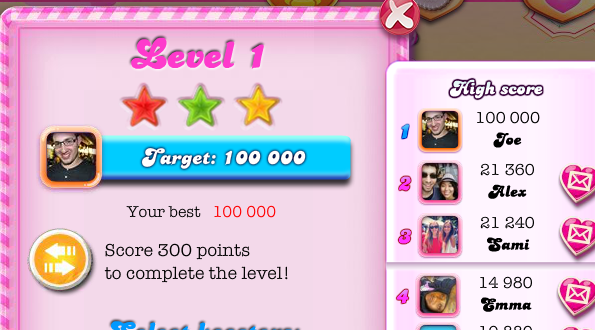

But back to the project at hand. At this point, the Chrome extension was all ready to ask Alice to prom. So I sent Bob the bits and the installation instructions. You can see the finished product in the video below:

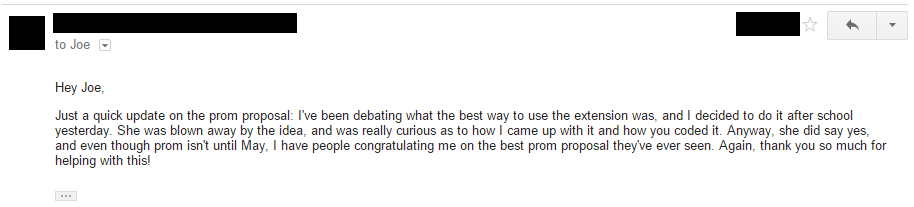

Oh yeah, and you may be wondering if Alice said yes. I’ll let Bob fill you in on that part of the story himself:

And of course, Bob held up his end of the bargain — here’s a picture of the happy couple at prom, thanks to Trivia Crack! (Faces hidden for privacy). Update: Making image much harder to reverse image search. Behave, people…

Still waiting on that first born child though. I’ll check back in a few years…

Interested in hearing about other side projects like this one? Subscribe to my blog and follow me on Twitter. I’ll let you know when I think of something fun.

Warning:

Warning: